After Marcelo Bielsa’s Athletic Bilbao were beaten 3-0 by Barcelona in the 2012 Copa del Rey final, Bielsa famously handed Pep Guardiola a dossier containing all the analysis he had collected in preparation for the game. It was presented as a sign of respect, a gift. Flicking through the pages, Pep was stunned: “You know more about Barcelona than me!”

“Simeone was crazy for Marcelo Bielsa, he loved him so much”

You’re probably going to be hearing that story a lot in the coming weeks, ahead of the two managers’ reunion when Leeds face Manchester City in April. It’s all very nice and lovely, as are most stories relating to Bielsa’s relationships with people who cite him as their footballing Yoda. But it was not the only time Bielsa suffered a 3-0 cup final defeat to one of his disciples that season, and a curious lack of detail surrounds the other match.

Diego Simeone has always been different. When listing his most influential managers, Simeone namechecked Sven-Goran Eriksson and Alfio Basile before concluding, “Bielsa taught me most.” But those lessons have been used to deploy a vastly contrasting style of football, Cholismo, in which his Atletico Madrid are more than happy to sit back, let the opposition make themselves vulnerable, and then leave them lying in the dirt. “The exact opposite ideas of mine,” was Bielsa’s description of it in 2019.

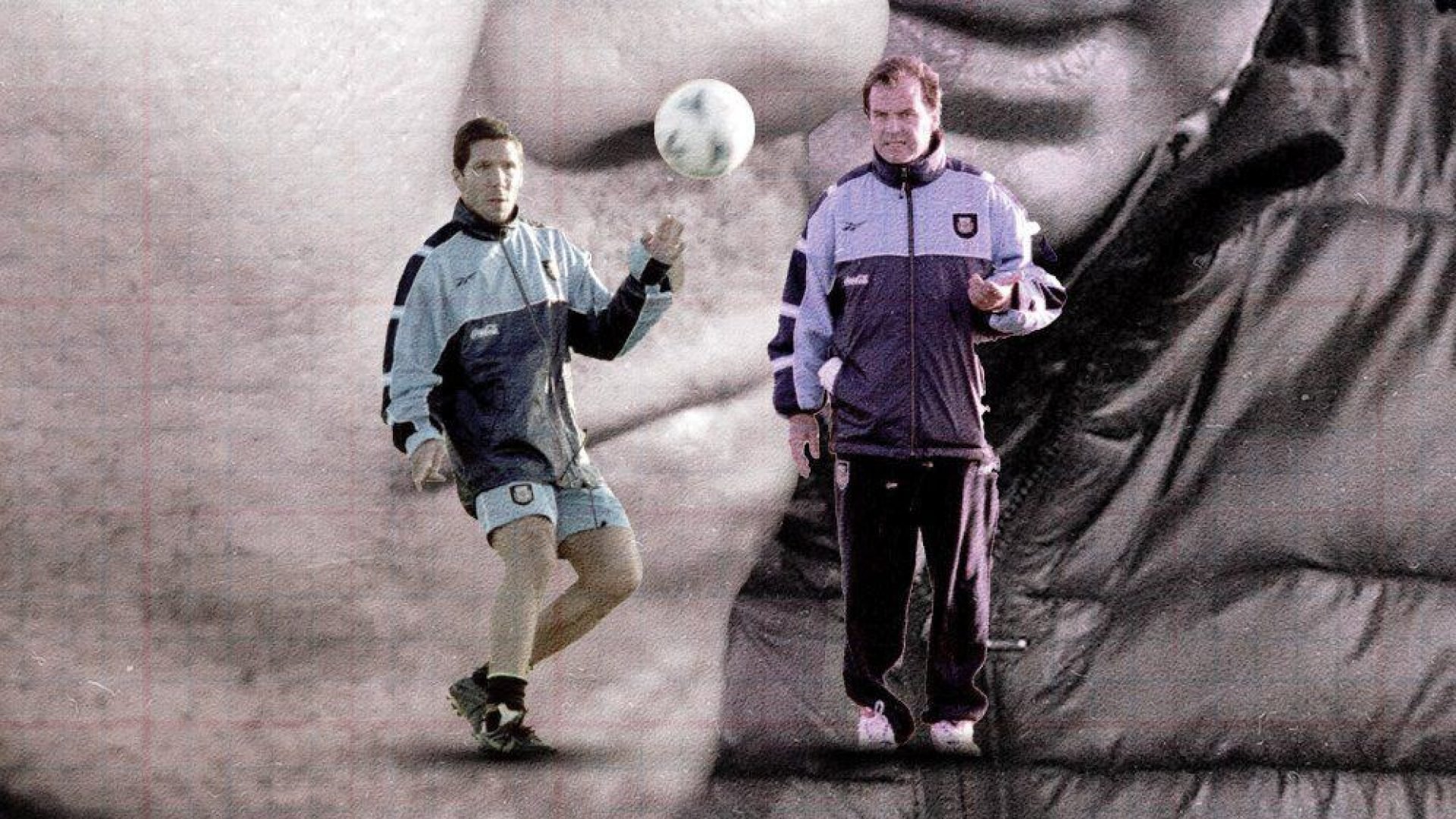

In his playing days, Simeone scored the first competitive goal of Bielsa’s reign as Argentina boss in a 3-1 win over Ecuador at the 1999 Copa America, and earned the last thirty of his 106 caps under his management. As Simeone’s former Inter manager Gigi Simoni told Planet Football in 2017, “He was crazy for Marcelo Bielsa, he loved him so much that he knew everything about him.”

But Simeone’s time with the national team came to an abrupt end when Bielsa’s Argentina failed in the group stages of the 2002 World Cup. The midfielder played all of the opening victory over Nigeria and the costly defeat to England, but was left on the bench for the draw with Sweden that eliminated them.

After the final match, Bielsa tried speaking to his heartbroken players, but could not hold back the tears. Up stepped goalkeeper German Burgos, who had played throughout qualifying only to remain unused in the tournament. “You cannot imagine the anger of someone who has played in all the qualifiers then been discarded for the World Cup,” Simeone is quoted as saying in Tim Reach’s biography of Bielsa, The Quality of Madness. “Yet he stood up and took the manager in his arms.”

Burgos is the uncompromising figure who Simeone trusted to be his assistant manager for nine years, until he left Atletico Madrid in 2020. It’s tempting to see the traumatic end to the World Cup as the moment Simeone separated the wheat from the chaff in his own mind, turning his back on Bielsa to form a pact with Burgos, a man who once threatened to rip Jose Mourinho’s head off if he tried any touchline shenanigans, and who after getting thrown out of the Vatican stood outside enjoying a cigarette. But both are complimentary of Bielsa to this day, and Burgos is credited as Atleti’s force behind one of Bielsa’s favourite pastimes, exhaustive video analysis.

Rather than roots in a heated World Cup dressing room, Simeone’s contrasting style, when compared to so many contemporaries influenced by Bielsa, appears to stem from his formative years as a player.

In Argentina, managers are expected to follow one of two paths. First is that of Cesar Luis Menotti, the chain-smoking idealist who guided the national team to World Cup glory in 1978 by preaching a style of free-flowing attacking football as a collective unit. Menotti viewed this as the antithesis of “right-wing football”, which “wants us to believe that life is a struggle. It demands sacrifices. We have to become steel and win by any methods … obey and function, that’s what those with power want from the players.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum stands Carlos Bilardo, the victorious manager of Argentina’s 1986 World Cup-winning team, who preferred pragmatism, cynicism, relentless hard work and meticulous research of the opposition. Diego Maradona could do the rest.

Bielsa is credited with combining the two methods to create a new brand of football, using the mechanics of Bilardo’s demand for graft from both his players and coaching staff to help him live by the philosophies of Menotti, who believed being a footballer was a privilege and therefore brought with it a responsibility to bring joy to those less fortunate.

Simeone does not appear to have quite so much time for the grey area between those two ideals. Not only did he win his first Argentina caps under Bilardo and also play under him at Sevilla, but he was also brought up at Velez Sarsfield, where he encountered Victorio Spinetto, whose own win-at-all-costs mentality formed part of the lineage that led to Bilardismo. “There they taught me values. Wash your clothes, respect, order everything that helps you in life,” Simeone later said. “From order you start living better.”

Simeone’s thoughts on Menotti, on the other hand? “Talking about Menotti would not be wise because I don’t know him in personal dialogue.”

These two contrasting styles, Bielsaball and Cholismo, came head to head in the 2012 Europa League final, held in Bucharest. In The Quality of Madness, a whole chapter is dedicated to the romance of Athletic Bilbao’s run to the final under Bielsa — storming Old Trafford in a blur of pass and move so emphatically even Fergieface couldn’t complain, inspired comebacks against Lokomotiv Moscow and Sporting Lisbon, even conceding Raul’s final European goal against Schalke — only for the final itself to pass by in two paragraphs. There is little in the way of extended highlights on YouTube, nor a replay of the full game itself. You can just about find the second half down the back of the sofa on Dailymotion.

Instead there is the bleak, depressing truth: Athletic Bilbao 0-3 Atletico Madrid. Two first-half goals from Radamel Falcao ensured Simeone’s side could sit back and allow Bilbao to do all the pressing in the second before picking them off with a final late strike from Diego.

The tone for the evening was set when 400 Bilbao fans mistakenly chartered a flight to Budapest rather than Bucharest. The UEFA stadium announcer added insult to injury for those stranded in Hungary by welcoming the fans arriving at the ground with the same, albeit less costly, faux-pas: “Welcome Budapest!”

While Simeone could rely on the same back five with which he later won La Liga and reached a Champions League final, Bielsa’s defence centred around Fernando Amorbieta. Two years later, Amorbieta was playing in the Championship after being relegated with Fulham; his main contribution to English football was being on the receiving end of a bite from Leeds’ very own Souleymane Doukara. You may or may not be surprised to hear that he was at fault for all three goals.

After the game, there was no present from Bielsa for Simeone, nor celebration of his achievement in taking Bilbao so far, past the previous season’s Champions League finalists and semi-finalists, across Turkey, Slovakia, Austria, France, Russia, England, Germany, Portugal and finally Romania. Just the same old recriminations of burnout — ignoring the fact Bilbao played 67 games in total that season — and whether Bielsa had been ‘figured out’ by opposition managers.

Bielsa did receive some support in the media, from none other than one Diego Armando Maradona, who told Marca: “For me what Bielsa has done is worthier than what Simeone has. Marcelo made a team out of nothing.” Sadly, even that was tainted by Maradona’s admission that he had fallen out with Simeone for letting Diego Sinagra, Maradona’s son from an extra-marital affair in Naples who he initially refused to acknowledge, train with River Plate.

We’ll see what Bielsa and Guardiola have in store for each other in the coming weeks, but when it comes to Bielsa and Simeone, there appears to be a mutual understanding that business is business.

They share enough similarities to know the score when the time comes for the whistle to blow. In the words of Simeone’s mentor Carlos Bilardo: “You have to think about being first, because being second is no good.” Or as Billy Bremner put it: “You get nowt for being second.” ◉

(This article was published in TSB 2020/21 issue 06 and is free to read as part of TSB Goes Latin.)

(Every magazine online, every podcast ad-free. Click here to find out how to support us with TSB+)© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us