Leeds United’s Australian tour has given us some odd sights, although sadly we’ve been denied the joy of Ezgjan Alioski hitting a eucalyptus high with his new family of koala bears, or a United reprise of Leeds Rhinos’ guest appearance on Neighbours. (Ian Smith, who played Harold Bishop, is apparently a big fan of the Peacocks but is no longer on the show.) But we have seen, as a club ambassador and at fan parties, Michael Bridges, former Leeds United striker, and former Leeds United pariah.

Twenty years ago we might have expected Harry Kewell to one day be posing for selfies with the fans travelling to Perth and Sydney — his wife, Sheree Murphy, did at least tick off the Neighbours cameo years ago. But then, there are pariahs and there are pariahs, and then there’s Harry Kewell, a player whose disgrace is so total that this week’s announcement of a decorative wall on Lowfields Road listing every Leeds United player of the last hundred years was followed by several social media announcements from fans determined to find Kewell’s name on the list and remove it. Even seeing his name typed out uncensored in this article will be enough for some fans to close the tab and read no more, and I don’t resent anyone if they do.

In 1999 Kewell was only practising to become the person that, one day, we would all hate. I recently watched two old games from the 1999/00 season, the two legs in the UEFA Cup against Roma; after the rumour about him coming out of retirement and signing for Leeds, I was curious to remember how we stopped Francesco Totti for 180 minutes. The answer was that we didn’t, but Alfie Haaland, Lucas Radebe, Nigel Martyn and, in the first leg, Jonathan Woodgate, so thoroughly closed his access to strikers Vincenzo Montella and Marco Delvecchio that Totti’s skills and passes were just bouncing a ball off a wall.

(Prefer this as a podcast? Click here to support Moscowhite on Patreon.)

Kewell scored the winner in the second leg and was the headline hero; he’d vied with Totti throughout to see who could have the bushiest half-mullet, who could arrange their collar with the least just-woke-up-like-Cantona care. Kewell was watched by Serie A scouts in Rome, provoking what was becoming a pavlovian response from his chairman, Peter Ridsdale, who started talking about giving Kewell a new contract, four months after his last one. Kewell will have been happy to hear that, but he didn’t mind the Italian interest either; he said he hoped to play in Serie A one day, not what fans who’d seen him growing up with Eddie Gray’s hand on his shoulder were expecting to hear.

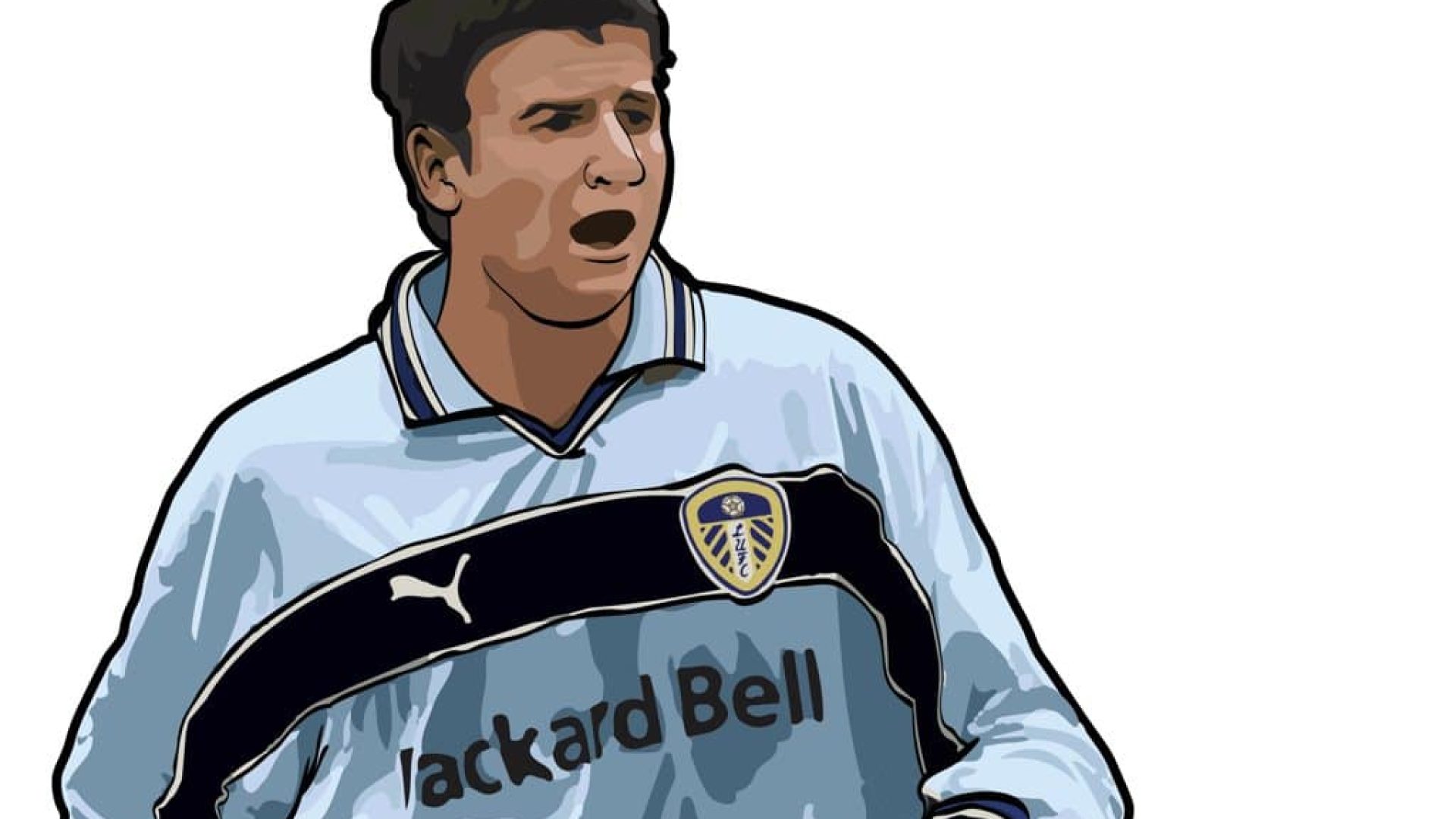

It was Michael Bridges who caught my eye in these games, though. He’d signed at the start of the season, and was just emerging from the shadows of Niall Quinn, Kevin Phillips, and Sunderland’s reserves during their promotion campaign, as the undisputed smash hit Leeds signing of the summer (Michael Duberry, Danny Mills, Darren Huckerby hadn’t made much impact yet; Eirik Bakke was exceeding expectations). He first bloomed, like Gary Speed, in an evening match early in the season against Southampton at The Dell. In 1991 Speed had pinged the tense trampolines of The Dell’s nets with two long range strikes; Bridges scored three, starting by controlling a header on the side of his foot and lofting a volley into the top corner, then stroking home a low cross from close range and finishing up by heading in a near-post corner. Later in the season he started celebrating goals by pretending to eat a sandwich, and Bridges was like that; despite his inventive delight when he controlled a football and suits that seemed inspired by the interior decor at Majestyk’s nightclub, artifice slid off him, revealing a 21-year-old player not yet come to terms with how good he could be.

Watching Bridges play against Roma, knowing how it will all turn out, made me want to weep. He and Kewell had the task of keeping the ball upfront and away from Totti to give Leeds’ back-line a rest, and while Kewell chose to aim counter-attacks forward at full speed, Bridges concentrated on possession. We’d seen Lee Chapman do this, backing his large arse into centre-halves while the ball bounced near his legs but out of his control. Bridges was different. He skipped and dribbled around some of Europe’s best defenders, beat them again to prove a point and buy some time, swivelling and swaying and throwing in one last drag back before drilling a pass wide to a teammate only he had seen running. Sometimes he’d decide faster, trying a no-look backheel to divert a pass down the wing to Lee Bowyer; once, the ball didn’t reach Bowyer, so a minute later Bridges tried the same thing again, and it did.

Alan Smith was just a substitute of inconvenience at this point, ready to irritate the defenders Bridges had made weary; Mark Viduka, the prolific Celtic striker, was being linked with a transfer to Bayern Munich. David O’Leary had made a clever signing, Jason Wilcox for the wing, so Kewell and Bridges could play through the middle together, Kewell trying to emulate Thierry Henry, Bridges already coming close to Dennis Bergkamp. It’d be funny how things turned out, if it wasn’t so damn sad.

Harry Kewell elbowed his way out of Leeds in summer 2003, taking advantage of new chairman Professor John McKenzie’s naivety to ensure he went to Liverpool and got the best deal for him, ahead of other clubs offering better deals for Leeds. Come winter Leeds were sliding towards relegation and, in the last days of the January transfer window, Mark Viduka agreed terms with Middlesbrough, Paul Robinson had a medical at Tottenham, and Newcastle bid heavily for Alan Smith. Only one player left, though; Michael Bridges, a few games into his comeback from three years of injuries, went on loan to Newcastle, who sent central defender Steven Caldwell on loan the other way.

“I felt I’d been a bit stale at Leeds and I’d been banging on the door to get out on loan,” said Bridges, who despite playing for Sunderland was a lifelong Newcastle fan. “My contract is up in the summer and I wasn’t offered a new deal. So whatever happens I won’t be going back there.” To Leeds fans stinging from what felt at the time like relentless battering, these words felt like another needless blow, as did Bridges’ reference to missing a one-on-one chance against Newcastle a few weeks earlier that would have earned a vital point; it was a good job he missed, he joked now, because he might not have got the transfer.

This was no time for quips. Bridges’ humour fell with a heavy clang in Leeds, followed by the falling tower of David Batty’s reputation, when he was rumoured to be the ringleader of players refusing to help the club by taking a wage deferral (Batty later put his side: he’d told the club they’d save more money, and have a better chance of staying up, if they sold the first team players who were thinking more about their lucrative summer transfers and put faith in those who wanted to stay). Lucas Radebe was trying to calm things down; but Seth Johnson was being booed for his performances, and there were calls for Eddie Gray to give up his job as caretaker manager so Kevin Blackwell could try to save the club. Nobody knew who our heroes were supposed to be anymore, but we knew Michael Bridges wasn’t one of them. In 2009 a thread about most-hated Leeds players started on a web forum, with Bridges at the top of the list.

The only one left who looked like a hero was Alan Smith, but Leeds supporting writer Rick Broadbent was wise before the fact in his report in The Times on the weird wake for Leeds and Smith at the end of the season’s last home game against Charlton, after relegation a week earlier. While Smith was mobbed by fans and lifted aloft, Broadbent was looking at Mark Viduka, sitting at the back of the West Stand with his son on his lap, scorer of 59 goals in 130 league games; compared to 38 in 171 by Smith. While the supporters clung to Smith, not wanting to let him leave, Viduka was “slipping away quietly to footnote status.”

Viduka had spent most of the season in a rage status, complicated by the serious illness of his father at home in Australia. When he was at Elland Road, Viduka was in Peter Reid’s office, telling the manager what he thought about his management, then in the dressing room, telling the players, too; “If you want to go down, stick with this fella.” He scored eleven league goals, seven of them in twelve league games leading up to the decisive Bolton match, when Viduka’s goals felt like all that stood between Leeds and the abyss; take those goals out and Leeds would have been ten points worse off. (Smith, in the same period, scored three goals, earning four points.) But his rage had become self-destructive; a second yellow card for kicking the ball away at Leicester to protect a vital win was followed by two yellows in the first half at Bolton when Viduka inexplicably self-destructed, and destroyed Leeds’ hopes with him. It said something about his quality and his commitment that without him there was no hope. But it said something else that Leeds fans now didn’t care if he left, so long as they could still hold Smithy.

Alan Smith had been raging since his debut, but it was never clear exactly what he was angry about. Maturity seemed to have made him more stupid, not less; while once he’d been able to get two Roma players sent off in one incident just by breathing near them, the red cards had all been coming his way for some time — in Valencia, in Cardiff — seven in all for Leeds, plus a two-match ban earlier in the season for throwing a bottle into the crowd. Now it was like everyone else had a route planner for getting inside his head. Despite that, his tireless running — no matter if for little reward — made him untouchable in the eyes of the fans, who at the end of the Charlton game all wanted nothing but to touch him and say goodbye. “There has not been a bigger hero here,” said Eddie Gray, whose own career made him more than worthy of consideration. But he was about to be sacked that night, with a game at Chelsea still to play, while the cheers for Smith still echoed around Elland Road.

What was strange about it all, as Broadbent pointed out, was the gap between Smith’s words and actions. He’d been asked about relegation the summer before, but insisted he wouldn’t leave Leeds, even if the worst happened. “It takes a better type of person to stay,” he said. Now, he was saying, “With supporters like that, it’s going to be hard to go away,” but, hard as it was, that’s what he was going to do. Instead of being the better type of person and staying, now he said, “If an opportunity to come back came along then I would grab it with open arms.”

Everyone seemed happy with that. Michael Bridges and Mark Viduka would never be welcome back; nor Harry Kewell, although we had no clue then of how firmly he would go on and bury himself. But Smith was lifted on our shoulders above them all as the hometown hero, who was going to do what he had to do, and then return. And that lasted for one more week.

“People say that Leeds and Manchester United are big rivals, but we’re not even going to be in the same division, so it’s not even a rivalry,” Smith said. “You sign for Scum, you don’t come back,” the fans sang, as Smith strolled around Stamford Bridge in the season’s final game. His reply to the fans was a one-fingered salute. And that was the end of another hero.

What we’d held up at Elland Road the week before was not a legend, or the greatest hero the place had ever seen, but an empty vessel onto which we’d projected our imagined version of what Leeds United players should be like. Like a mirror ball Smith reflected that light back onto us, and we each danced in our particular slice of the glow. But if you hold a mirror ball too high and drop it, you’ll find it smashes into a million pieces, and that the inside was hollow all along. Sweep the pieces into a dustpan and deliver them to his next club.

It’s good that Michael Bridges is grinning with the fans in Australia now, and that Mark Viduka is appreciated again as a phenomenal goalscorer. Their crimes against Leeds were, in retrospect, minor, at a time when everything that happened at Leeds happened in a major key. Bridges lacked the guile to hide his jokes about doing Newcastle a favour, and was too honest to pretend he wasn’t frustrated by not playing for Leeds; I still don’t know what was going through Viduka’s mind at Bolton, but I do know that without his performances in the previous two months, Bolton would have been an irrelevant day anyway. Bridges and Viduka were guilty of mistakes in words and in deeds and on the football pitch; set against Smith’s unrepentant attitude as he crossed the Pennines, and Kewell who defined a category all of his own, they barely deserved to become the pariahs they were. There’s even a case for Smithy, although it won’t be me that makes it.

But all this, I think, has something to do with this coming season, when Leeds will be seeking promotion, and Kiko Casilla, Liam Cooper and Gaetano Berardi, who many fans wanted tarred and feathered after the play-off semi-final, will be seeking absolution. Shambolic defending against a multi-million pound forward-line in Australia this week didn’t help their rehabilitation, but the uneven environment of a made-for-showbiz friendly game seems a perverse venue in which to form judgements. Leeds United’s future — and theirs — doesn’t depend on being able to contain Pogba and Rashford this season, but on being able to contain Luton and Stoke, and on putting right the wrongs of last April and May when April and May come round again. Reputations are formed, but they’re not fixed, not when there’s still football to be played. ◉

(Are you reading the BUFF? A daily email newsletter by Moscowhite for twenty pence a week. If you enjoy these reports, your money supports more: Click here to get your daily BUFF.)

(artwork by Dan Marsham)

[x_recent_posts type=”post” count=”3″ orientation=”horizontal”]

© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us