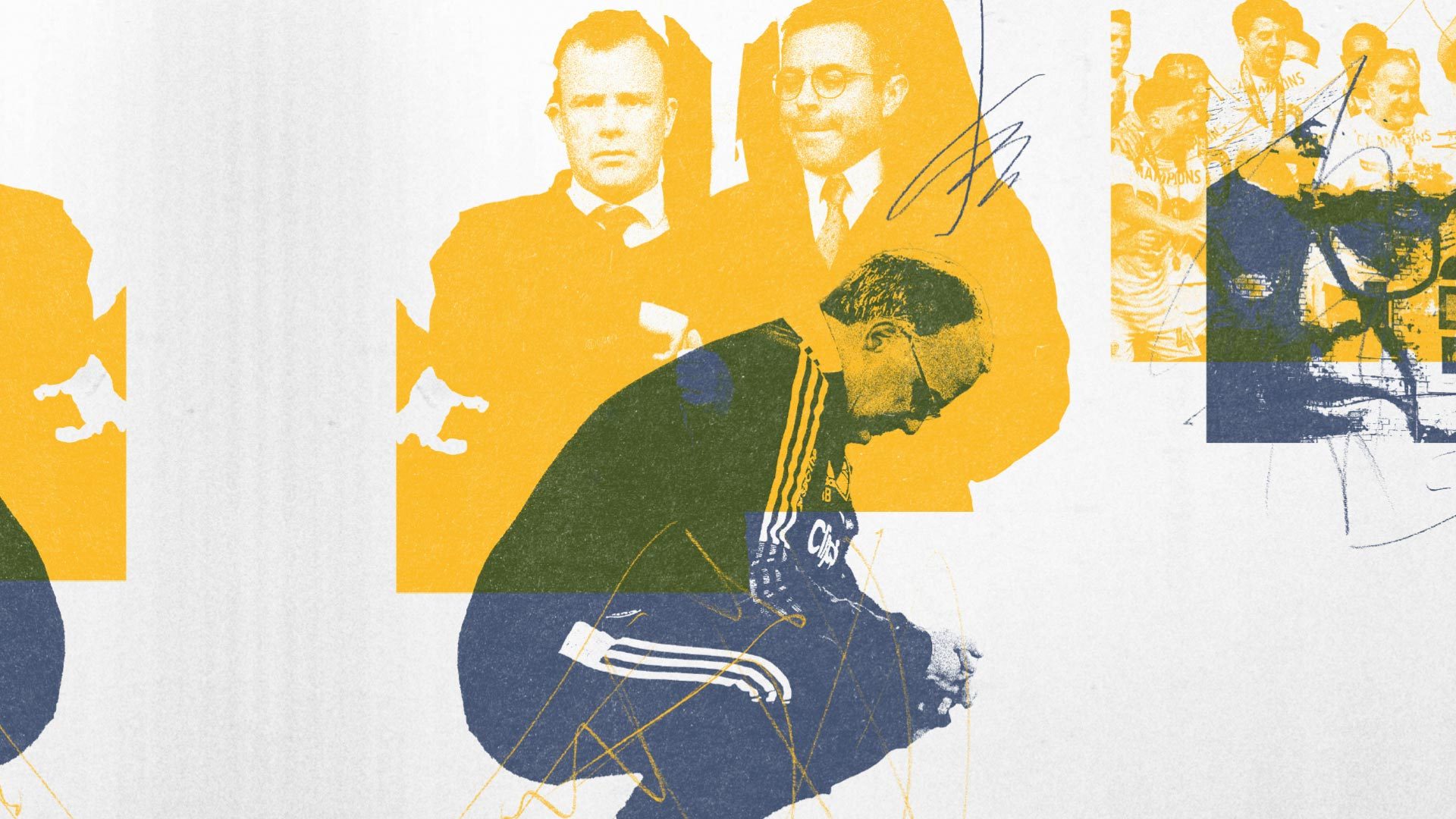

One of Marcelo Bielsa’s sayings is written on a wall in Leeds Six, next to a building high mural of the sacked Leeds United coach. ‘A man with new ideas is a madman until his ideas triumph’, it says.

Before the Tottenham Hotspur game, his last in charge at Elland Road, he said yet another thing that ought to be remembered, summing up the fate of a football coach as well as anything I’ve ever heard: “You have to undo what works before it stops working.”

From madman to genius to madman again, but all of that is perception. What Bielsa did, who Bielsa was, didn’t change, neither before, during or after his triumph. When he arrived in Leeds, people didn’t believe in him, no more than they believed in Steve Evans or Paul Heckingbottom: proof was needed. One week of proof — Stoke 3-1, Derby 4-1 — then three years of proof. Marcelo Bielsa was a genius. Then, as the richest league in the world reasserted its might over his hobbled together Leeds, the team lost games, and he was a genius no more, they said. Once the games were lost there was no chance of recovering. As Bielsa says, the job of a coach is to keep fixing things forever, before they’re broken, at which point it’s obvious to everyone what the coach should have prevented. Football doesn’t only demand genius, it demands your foresight defeats its hindsight every single week.

This is one of the tragic parts of Bielsa’s sacking. The way he laid out, press conference by press conference, how all the worst elements of football conspire to make that outcome inevitable. In the end perhaps his greatest mistake was thinking for a moment that Leeds United could overcome the sport’s worst excesses. He was different, Leeds was different, together they succeeded. Perhaps, in West Yorkshire, people were listening, and willing to keep being different.

An unspoken fear of failure rots football from within. Andrea Radrizzani tried to present the ‘toughest decision’ to sack Bielsa as brave, but the truth is, the board were frightened. Money, as always, is the bastard. The economic cost of relegation from the Premier League puts terror in the heart of every bottom half club. Pre-season confidence becomes panic by October as club after club realises their careful plans for success will only be good enough for mid-table at best, and starts frantically obsessing about the worst.

Leeds, for a time, resisted. Bielsa had reasons to think Leeds would be different. The story goes that he was packing his office up after the play-off defeat to Derby in 2019, and senior staff had to make an urgent trip to Thorp Arch to tell him that failure wasn’t the end. This season, the board held on through the October stress test, the natural opportunities for change suggested by international breaks, the January transfer window. They were being as brave as Bielsa’s football demands. Then a quirk of Covid postponements and the fixture list put Liverpool away between Manchester United and Spurs at home, and their bottle went.

In a way there’s no embarrassment in doing what every other club does. But shame is the only word when you have to put down the plastic ‘This is Leeds’ flag and admit that being Leeds doesn’t make us as different as we hoped. The story of Leeds after promotion, after sixteen years, has been about how long this weird anachronistic club, its mind never far from 1975, could resist adaptation to the modern top-flight. Last season’s objections to the European Super League suggested an organisation as firmly Against Modern Football as the hoodie Victor Orta once wore in the away end at Hillsborough claimed. Glam-rocking through the Premier League with Gjanni Alioski like a platinum Bowie in white, maroon, green and lilac, Leeds were four to the floor throwbacks and even the modernised bits of Elland Road barely noticed the latest decade: remember the cashless bars this season, that lasted a game?

The story won’t last much longer and it can only end one way. They’ll get the touch screen order points working one day. The alternative is relegation. The Premier League is too strong to allow its clubs to retain too much brand-unfriendly identity. Its strength is its money, and the Football League’s lack of it. Bielsa wasn’t sacked for losing games, he was sacked because the eventual result of losing games is poverty. If the Championship was as rich as the Premier League, or close to it, relegation might be more like what it should be, a sporting failure that fans of other clubs can mock. Instead it’s an existential threat at the bank, and that’s what matters most.

Bielsa, knowing all this, explained several times how to fix it. Everyone at the top level of football should stop being greedy and agree to make less money from the game, he said. More money could then be invested in grassroots football, in developing excellent young players and coaches. Supply and demand means the more excellent players and coaches there are, the lower the transfer fees and wages needed to hire them. If Premier League clubs already have full squads of world class players, but there are many more available, those players can go to clubs in the Championship and lower down. The quality of games at all levels improves, increasing crowds and broadcasting revenue for good-to-watch lower division football. Players have less incentive to transfer away from their home towns, creating stronger links between teams and local fans and communities. The Football League becomes an attractive, healthy competition, and relegation no longer wipes 75% from a Premier League club’s value overnight. And managers like Marcelo Bielsa, with a team near the bottom of a division, can be given security to play their way to safety. An idea could last longer than three months.

It’s not utopian, it’s simple, and I’m sure most Premier League chief executives, wincing at the contracts they’re handing to players, would rather put that money into youth development, strengthen the leagues, reduce the risks attached to their own failures. But Angus Kinnear, presented with similar ideas in the fan-led review of football governance as those his own head coach regularly proposed, lambasted them using hysterical comparisons to Chinese famines under Mao. He wasn’t the only dissenter. That’s because Premier League chief executives are stuck between greed and fear, constantly under pressure to make as much money as possible, constantly terrified of losing their cash-cow whether it’s to the Football League or a European Super League. Their fear reduces a fun sport that fans should enjoy watching to a static non-game riven by financial paranoia, while twenty clubs all kid themselves brave by boasting that they’re in the league to win it.

What is fun about watching Premier League clubs playing their frightened, greedstruck matches? Again, if Bielsa’s ideas were heard, the game could be reorganised closer to what it actually is: a game you’re going to lose. Football presents itself as a game of winners. But only one team can win the Premier League each season. The nineteen other clubs are all losers, and to put such an unlikely outcome as ‘winning’ at the centre of the sport is a Quixotic flail against the odds. Winning should be the goal, but losing, rather than disaster, should be recognised as the norm. “I know that joy after winning only lasts five minutes,” Bielsa once said, “then there is a huge void and a loneliness that is hard to describe.” Yet we build the sport around chasing five impossible minutes of joy, while only Bielsa, the idealist, is realistic enough to think about how to survive all the time when winning doesn’t come.

A sad lesson of Bielsa’s time at Leeds is that, in the Premier League, to listen is not to understand. Bielsa never managed anywhere for so long, and because media demands on Premier League coaches are so great, he has rarely explained himself at such length. His insights were held to be part of his appeal, a pride for Leeds that he spoke so well on our behalf. Did anyone listen, though?

This season’s back and forth about using youth players suggests not. When challenged about why Joe Gelhardt, Cody Drameh, Lewis Bate or Crysencio Summerville were not getting more use in the first team, Bielsa pointed out that the Premier League is the hardest league in the world to get into, for teams and players, but that young players at Leeds were getting more chances than they would at most other Premier League clubs. He’d tell the journalists asking the questions to check the numbers, but they never did, so the cycle of questions continued without anyone looking up the answers. The answers are as follows: that of players aged nineteen or under, only Valentino Livramento and Anthony Elanga have had more Premier League minutes than Gelhardt this season; that in the top twenty, Leeds have four players, more than any other club. The Premier League, as a whole, is youth-averse — Brighton’s Jeremy Sarmiento is 20th most used, with 21 minutes — but this was Bielsa’s point, too: that hardly any team in the Premier League is giving much playing time to teenagers, but Leeds are giving more minutes to more teenage players than most. And still you ask every week why they’re not getting more chances.

By confining his efforts to football, perhaps Bielsa condemned himself to a career of being heard, but not listened to. That he speaks seriously at length about important topics makes the people around him feel good by association — our manager is cleverer than yours. The Premier League lusts for that surface. His intelligence was sold for glamour. But that doesn’t translate into thinking about what he has to say, so conventional thought still wins in the end.

Bielsa’s ethos can be summed up by a training pitch lecture to a young Benjamin Mendy, filmed while they were both at Marseille. Mendy, evidently, did not take it in.

“[Mendy] already knows he will be a millionaire, he also knows that he will be a star … but there is no certainty that he will be the best. You laugh, because you think I am making a joke … Being the best, it takes away happiness. It takes away hours with your wife. It takes away hours with friends. It takes away parties. It takes away fun. You have a very big problem. Very, very big problem. You have money. But you don’t have time to enjoy that money you have, and to enjoy what money gives you in terms of happiness. You would like to buy time. So, success, it takes away the possibility of being happy. But that is a choice, it is also a choice … You can choose. If you choose that you don’t want to be the best left-back in the world, what is the problem?”

Leeds United, in the end, asked themselves that question, and decided that if they didn’t want to be Bielsa’s club, then there is no problem. Bielsa’s is not the only way. Other managers have won promotions, other clubs have survived in the Premier League. They’ve done it without working anywhere near as hard as Bielsa made Leeds work. But the others have done it without gaining the plaudits, without the pleasure, without inspiring murals or international attention and devotion. They haven’t inspired the same economics, either: when he was confirmed for his second season, the club’s marketing campaign on billboards across Leeds was for ‘Marcelo Bielsa: Season Two’, not ‘Leeds United: Season 100’. Neil Warnock could have got this club promoted. Maybe even Paul Heckingbottom — his Sheffield United are 5th now. If you choose not to be Bielsa’s club, what is the problem? You can still go up, still be in the Premier League. But Leeds United benefited immeasurably from being Bielsa’s club. He made them go through with the sacrifices, knowing they wouldn’t be able to enjoy it along the way. That’s how come, when he embraced Kalvin Phillips after promotion was confirmed, he could tell him, “Kalvin! The best!”

Doing things the hard way was Leeds United’s chance of rising above the humdrum, until the club gave in to the truth of a lie it always told itself. Finishing 17th would be fine, we reckoned, as long as Leeds was in the Premier League. That was what Bielsa, with a budget supporting exactly that outcome, was delivering. But finishing 17th, most seasons, means losing twenty games. There’s no fun, there’s no parties, there’s no happiness, but in this league of losing there is the success of achieving the target, and Bielsa — thousands of miles away from home, away from hours with his wife, family and friends — might be the last to understand that, in elite sport, you can’t have your cake and eat it. The overwhelming feeling of this season has been that it has not been as much fun as the previous three, but Bielsa, in a twenty-team league in which only one of a handful of billionaire clubs can win, never promised anybody a good time.

Bielsa delivered exactly what Andrea Radrizzani asked of him. Introducing the new coach in June 2018, Radrizzani said Bielsa was being hired:

“…for the desire to change mentality in the club, and do it in a strong way, with a man who can bring innovation to improve the football [and] the players, but also in the way [we] run the entire football department and the academy. We believe that his philosophy and his vision reflect our desire to become a winning club and affect the mentality of the club.”

Over the next three and a half years that’s exactly what happened, but success in 2020 meant delivering Leeds into a competing culture in the Premier League that could be stronger than Leeds’ new culture. Bielsa, clear-sighted, warned of it. He proposed solutions for it. He kept the team performing, up to 9th, in spite of it. With the club’s backing, with its mentality rebuilt and reflecting his philosophy, he might have expected the work to continue, as hard as it was, of keeping Leeds United above the self-defeating paranoia of the Premier League, instead of sinking into fear. But the board were not as brave as him. So they sacked Bielsa. And as the sun set behind his mural on Hyde Park Corner on the eerie Saturday afternoon after Leeds lost to Spurs, it felt like nothing Bielsa ever said was ever heard here at all. ⬢

© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us