Everton fans are lucky to have in their repertoire one of BBC television’s Wednesday Plays, made in 1968 by Tony Garnett and Ken Loach, the producer-director combo who upended television drama two years earlier with Cathy Come Home and its raw depiction of homelessness. In The Golden Vision Everton is the muse, but to an extent that was circumstance — Garnett was a fanatical Aston Villa supporter wishing he was making this in Birmingham, but the writer, Neville Smith, was all Everton. The subject of the drama was football fans, with documentary contributions from football players, the blurring, duelling realisms a hallmark of Garnett and Loach’s approach.

The fans’ parts are all acted, but authentically, and part-improvised, by a cast of amateurs recruited from Liverpool’s social clubs by producers who went to see local talent shows. Attention to realism was how you could get someone mumbling “gobshite” on 1968’s BBC. One moment stands out from modern fandom: Everton fans in the back of a removal lorry going down to London, singing of Liverpool’s Ian St John and Everton’s Alex Young: ‘St John’s body lies a moulding in the grave, as Alex Young goes marching on’. You don’t tend to get many songs about one centre-forward triumphing over the death of another these days, but maybe if we bring the folk hymns back that will bring back the gore.

Not everyone thought the blurring realism made for a believable play. The TV critic of the Reading Evening Post thought the stories were too ‘hard to accept’ as true to life, because surely not even the most ardent football fan would go to a match and leave his wife in labour. He thought presenting these fantastical episodes so realistically that they looked like documentary was very unfair on football fans. A reader wrote to the letters page next week to help him out, saying he’d anticipated, ‘the clicking of switches as bewildered southerners changed channels … I also was a little puzzled, but only by the excellence of the acting … It was not just fiction, it was, believe me, Liverpool.’

The most touching of the criss-crossing domestic storylines is about an elderly fan who nobody believes when he talks down the pub about Alex Young scoring Everton’s winner in the 1906 FA Cup final, because they’re assuming the old boy is getting mixed up with their 1960s hero of the same name. One young schoolkid believes him, though, and goes to visit daily, making him cups of tea, listening to stories of life as a merchant seaman, and passing trivia tests on Everton teams of the 1920s. Here’s a brilliant bit of the script: “Twenty-first of April nineteen-hundred-and-six it was,” the old man tells him. “That was the year of the big San Francisco earthquake. A terrible disaster, that. But it was a disaster for Newcastle that day as well when we beat ’em one-nothing.”

The idea is to get across to unenlightened viewers in Reading what it means to be ‘football soft’, as one of the despairing female characters calls her husband. There’s a clear gender line, the women in the play a condemning chorus against their Everton obsessed husbands, sons, sons-in-law and their mates. Obsessed, as a word, doesn’t adequately express the way football dominates their lives, so we need stories to do the work. In just over an hour football goes up against birth, a new father shambling to his young wife’s bedside the day after an away trip to Arsenal, pointing at the crib and asking, “Is that ‘im?”, and wins. It goes up against marriage, a best man coming out blurred in every photo as he rushes to make the second half at Goodison Park, and wins. It goes up against sex, the fans talking football through a Soho striptease after that trip to Highbury, and wins. It goes up against work, fans begging for early release from drudge so they can get to the match, and wins. It goes up against death, a hearse giving an Evertonian his final trip around Goodison Park while a game goes on inside, and wins. Eventually a priest shows up in the front room, wanting to know if football on Saturdays is keeping the men away from Sunday morning mass, and going up against religion, football wins. Birth, marriage, sex, work, death, religion and salvation in the hereafter. Football has beaten down and replaced them all.

When that is interwoven with interviews with Everton’s actual players, such consuming football passion turns ominous. Three players are filmed on the train down to that same Arsenal game. “Let’s face it,” says World Cup winning left-back Ray Wilson, “The game has got so big, results mean everything now. You get one or two teams like West Ham, everybody wants to play West Ham, simply because you know you’re going to get a good open game.” If you’re thinking that sounds a bit like Bielsa’s Leeds in 2022, I think you’re right. “I’d like to see more teams like West Ham playing,” says Wilson.

“People are going out there playing under pressure, knowing that the result is all important,” adds the captain, Brian Labone, as Wilson smokes a cigarette beside him. “And football has been sacrificed for results. It’s not all of my decision to retire,” he says, about intending this for his last season, “but that is part of it.” Fans are sacrificing everything, life, marriage, death, the rest, for football; but football is sacrificing itself for them. Players are replacing deities, but they can’t cope with the madness of what they’ve made. That what they’re saying in 1968 sounds so familiar in 2022 makes it seem likely as true in 1906, football’s permanent dilemma.

“It’s the fear of not having success, isn’t it?” says Wilson. Gordon West, the goalkeeper, adds, “I don’t think many footballers, now, in the First Division, really enjoy the game. I certainly don’t enjoy the game.” Later, in a voiceover as he’s filmed making saves against Arsenal, West continues: “I don’t enjoy playing at all on Saturday. From three o’clock on til twenty to five, I just can’t wait for it to finish.”

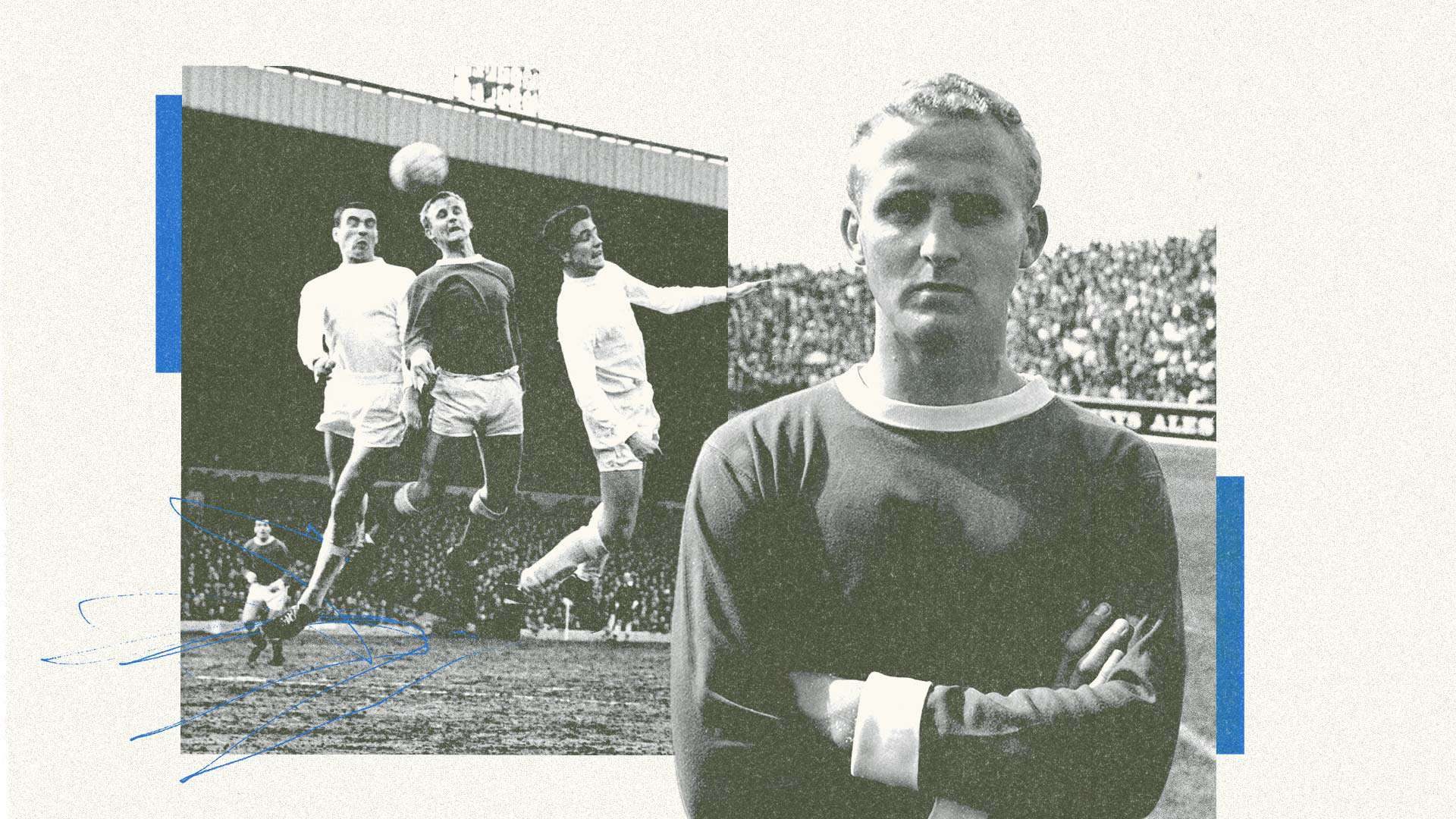

The ultimate expression of the football dream being crushed by pressure into boredom comes in interviews with the striker whose nickname titles the play. It was given to Alex Young by the Spurs player turned journalist Danny Blanchflower, talking about, “The view every Saturday that we have of a more perfect world, a world that has got pattern and is finite. And that’s Alex, the Golden Vision.”

He looks the part, with curling yellow hair, tall, dour in expression and gentle of voice, but with expressive football skills that made him a fan favourite despite his average scoring output. When the manager, Harry Catterick, dropped Young in 1964, fans threatened violent retribution against him and one marched on the pitch with a placard reading ‘Sack Catterick Keep Young’. In the interviews, Young talks about his working class upbringing in Scotland, becoming an apprentice mining engineer, playing part-time for Hearts; the idea is to bring his life into close parallel with that of the fans, a working man, but one football has helped to do a little bit better. Without football, he says as he’s filmed getting into a Mini, he doubts he would have a car. “I’d be doing reasonably well, but not with a great deal of prospects.”

What prospects he has in football seem temporary. “Next week sometime somebody comes along, and bingo, you’re transferred. I don’t know any professional footballer who feels absolutely secure. I think this is a point about professional footballers, we all feel very insecure. Because it’s a job, it doesn’t last forever.” His influence on his own career can feel minimal. “I think I’m a bit erratic sometimes,” he says about his own performances. “When I’m on, I can play as well as anybody … then sometimes I sort of drop down to the depths a bit, I can’t understand it myself, I’ve tried to think about it, but it just happens. And sometimes I’m not as good. Other times I’m quite good.”

And on such mysteries men in his town build all meaning in their lives, while Young looks for something that means as much in his. Combining work and football as a part-time player at Hearts, he says, “I used to enjoy it quite a lot, because it was sort of a change, you would go to your work and train at night and then a couple of days off in the mornings … I don’t think it made any difference to me in fitness, I felt just as fit being part-time professional as full-time.

“When you’re full-time professional you have a lot of spare time in the afternoons, and you get bored, drink cups of tea and that, and I don’t think it does you much good.” When he’s filmed at the other end of the journey in his Mini, he’s gone to do an hour of football coaching at a primary school. “I find it’s very rewarding,” he says, almost sounding relieved. “At night I felt that, well, that was worthwhile that. I enjoyed that day. Other days when you’ve done nothing you say to yourself, is it worthwhile, what’s it all about?”

The Golden Vision every Saturday of a more perfect world, that’s what it’s all about. The play’s ending is a daydream, as one of the fans on the Goodison terraces slips into a mid-match reverie, imagining Everton’s coach coming to him, pleading for help in an injury crisis, giving him Alex Young’s number 9 shirt to wear. As he dribbles around tackles, the crowd sways this way and that for a view of the ball, until he stumbles and V-signs of frustration fill the screen. But in the next move he plays the ball out wide, then gets to the cross, and powers a header past Sheffield United’s goalkeeper: the crowd roars, the Everton players mob him, and a toothless balding overweight middle-aged factory lad with a dream that has a longer history than his marriage lifts his arms to take in the adulation of the crowd. Birth, marriage, sex, work, death, religion. Football has beaten down and replaced them all. But what about the real number 9, where is he? “After a few years, when you weigh it up,” says Alex Young, “you think, well, maybe there’s something better you can do.” ⬢

(Every magazine online, every podcast ad-free. Click here to find out how to support us with TSB+)© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us