Long before the 49ers Enterprises linked Leeds United to an NFL franchise, Elland Road was the home of an American football team. Back when John Sheridan was swaggering in midfield and Billy Bremner was managing in the dugout, for a solitary season in 1986 United shared their ground with the Leeds Cougars. In their decade of existence, the Cougars bore all the hallmarks of an archetypal Leeds team. Their uncompromising approach earned them vilification by outsiders as the ‘bad boys’ of their competition, and made them enemies of match officials and league administrators. Places like Manchester and London had more teams, but Leeds remained a one-club city with a devoted army of supporters. And like all great Leeds sides, the Cougars had plenty of promise, and a knack of falling short. If a team had to be known as the best to never win the Bowl, they were destined to wear blue, yellow, and white.

Interest in American football boomed in the UK in the mid-1980s, when Channel 4 began broadcasting NFL matches, providing an audience living in Thatcherite Britain a glimpse of the impossibly exotic American Dream. “The only thing I can really remember is the sun always seemed to shine when you watched the 49ers,” says Mick Hardaker, who played 102 times for the Cougars between 1984 and 1991 and was also the club’s chairman. “I loved watching Joe Montana. I never saw him playing in bad weather.” Casual viewers became fevered fans, engrossed by characters like the Chicago Bears’ 24 stone defensive tackle, William Perry, better known as The Refrigerator; and the 49ers’ Hall of Fame quarterback Joe ‘Cool’ Montana, who led the team to four Super Bowl victories and was the first player to be named MVP in three.

“I started watching on Channel 4 and then a friend of mine in the ambulance service went and started playing up at the top of Meanwood Road,” says Hardaker. “We trained for a few months, then played one exhibition game at Roundhay Park, in front of about 60,000 people for the Lord Mayor’s Parade day. That was the first game! It took off from there, and I was amazed at how it gained momentum. But I’m sure that was because American football on Channel 4 was really popular.”

Mark Raynor was a teenager living in Castleford when he chose to support the New York Giants at random. “Fortunately, they won the Super Bowl the year after I started to support them,” he laughs. After hearing about the Cougars, he became one of their most devoted supporters, later setting up a website detailing the club’s history that serves as a time capsule of the decade.

“I was fifteen. They played at Bramley when I started going, so it was four buses just to get there for me. It was exciting because it was new. There was nothing at that time, there was no internet, you knew nothing about it. You couldn’t easily catch up on something. I suppose when you’re fifteen, sixteen, and your mates don’t know anything about it, then I’ve got one up on them!

“I mean, it was all homemade. I suppose it’s like an amateur football club. It was all done by people who loved doing it. I think there were just over 200 clubs around the country at one point. And basically it was just people who’d seen it on the telly, heard about it, and thought, ‘We can do that. We’re big fat rugby players. We can do that.’ And it just took off.”

The Cougars switched homes throughout their existence, playing at Bramley Rugby League’s McLaren Field, Odsal Stadium in Bradford, and West Park in Leeds at various points. Hardaker was able to secure Elland Road for a season after getting to know long-serving groundsman John Reynolds. “As a lifelong Leeds fan, I couldn’t believe it, running out at Elland Road,” he says. “We were getting about 1,500, up to 2,000. We were only using the West Stand. 2,000 was great at Bramley, but you get 2,000 at Elland Road and it just feels a bit weird. It’s sort of like an empty cathedral. We played at Odsal stadium for two years, which was phenomenal. We had crowds of 3,000 turning up at Odsal.”

Because of the profile of the players and lack of familiarity with the sport, the UK iteration began predominantly as a running game. In Tiggy Bell, a roguish character who later had a spell in prison, Leeds had one of the best running backs in the country. “He was a character and he was always gobbing off, even to the coach on the sideline,” says Raynor. “I’d be thinking, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ It’s an amateur game. They wouldn’t stand for it if it were a professional.”

As a lineman, Hardaker’s job was to protect his running back. “Me and Tiggy used to not see eye to eye regularly,” he says, “but he realised that he needed me and Jerry Hopkinson, because we were the inside blockers. It’s easy not to block and let somebody get absolutely annihilated as they hit the hole. But yeah, he was a phenomenal player. One of the best British running backs. Just a spiky character.”

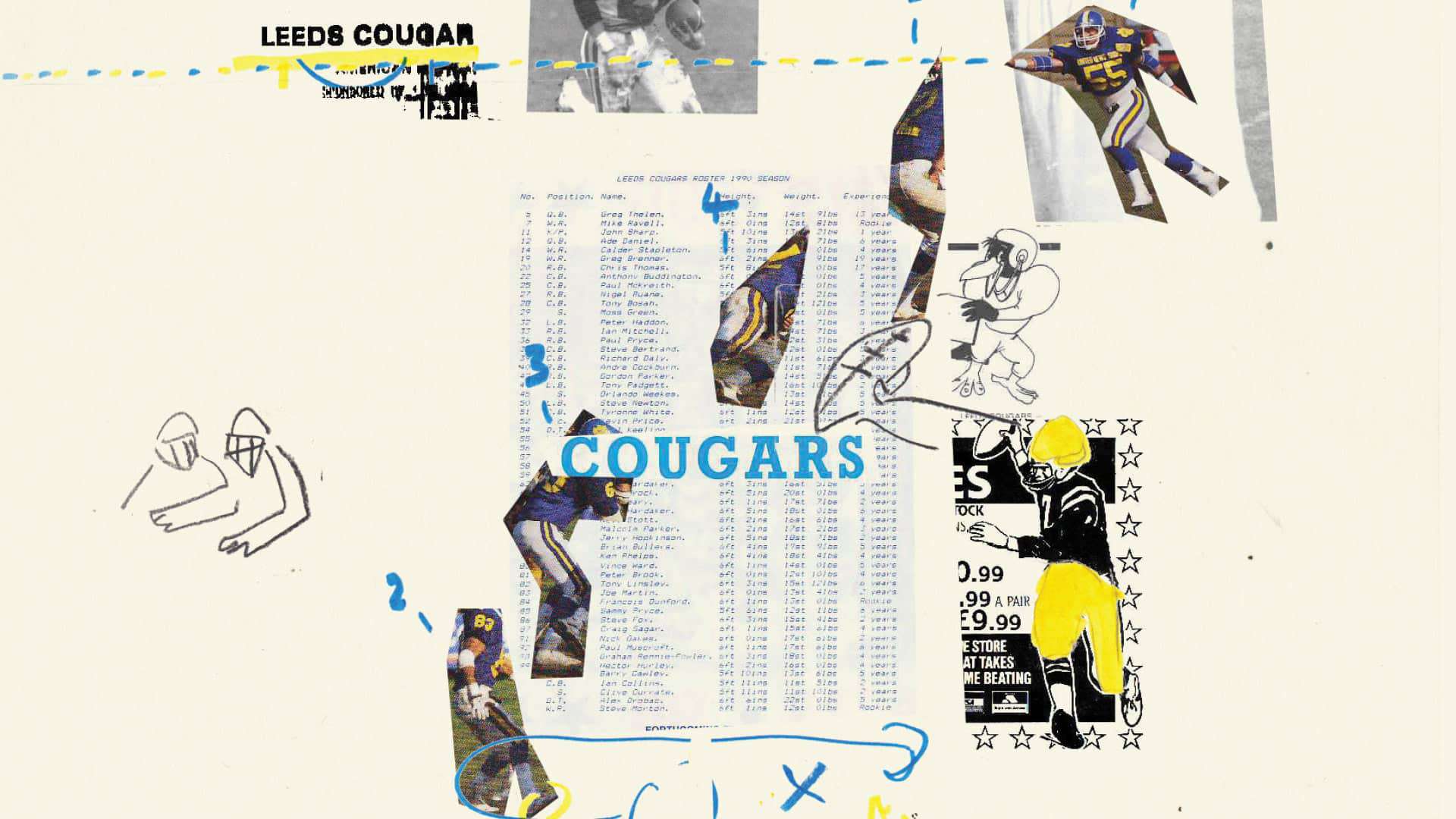

Teams were soon able to attract semi-pro American imports, naturally favouring quarterbacks who could become the brain of the side and introduce an aerial passing threat to their game. “We managed to pick up a guy who lived in Florida, Glenn Stevens,” says Hardaker. “Glenn played quarterback and between him and an outstanding wide receiver called Sammy Price we became known around the time of playing at Elland Road as the Air Cougars.

“Them two just passed and passed and passed, but we had a big line so we could grind it out as well if we wanted to. I’m 6’5” and I was about nineteen stone. I was the smallest of the line. Someone from Manchester said, ‘Your line needs a Yorkshire rose with a needle through it.’ We were all clean, we were just big lads who lifted a lot. When Gregg Thelan came it was different again, because he could pass a ball through a tyre at forty yards.”

Gregg Thelan grew up in a small city in south-east Wisconsin called Oconomowoc, about an hour’s drive from where recent United head coach Jesse Marsch was born. He played college football for North Michigan, where he took over as quarterback from Steve Mariucci, who later became head coach of the San Francisco 49ers. When he was first approached about joining the Cougars, Thelan was playing for Jesse Marsch’s hometown team, the Racine Raiders. They share a sunny outlook: he replies to my emails by signing off: “Make it a great Wednesday! Make it a great day, Gregg.”

When his coach at the Raiders, Norm Killion, first suggested playing overseas, Thelan’s initial reaction was to ask, “What are you talking about?” He was in his mid-twenties when he moved to Leeds in 1989, and the Cougars were being coached by fellow American Chuck Brogdon. As a semi-pro, Thelan was provided with flights, accommodation, a car, and a small wage. He lived above a chip shop near Leeds city centre in his first year before moving to Wortley in his second, supplementing his income by working in a gym and on the door at Harvey’s wine bar, which was being run by Brogdon and his wife.

There was scepticism of imports when they first joined. “They came across not really expecting the standard to be as high as it was,” says Hardaker. “When you get here and you’re Gregg and you thought it would be fairly easy and the first game you get smacked in the mouth by a 6’6”, 200lbs defensive tackle, you realise, ‘This isn’t what I expected.’”

Thelan could hold his own, particularly after being given a typically warm welcome to Leeds by a certain Vinnie Jones. “We did a thing with Budweiser, who sponsored the league, at Elland Road,” he says. “Some deal with — in air quotes — the world’s longest pass completion. John LaFleur (another Cougars import) and I did it. And you guys had just signed a guy by the name of Vinnie Jones. He wasn’t a big dude, but you don’t have to be to play soccer. We were there with all our kit on. And of course the hooligans were, you know, ‘Hey, you puffs,’ all that kind of stuff. And we’re like, ‘Just shut up, get the job done.’ Seventy-something yards, I think I threw it. I used to do over eighty until I messed up my thumb.

“Vinnie came out to warm up and we were still on the pitch. He went, ‘Get off, come on, we got to warm up. We’re ready to go.’ We didn’t understand that. John said something to him. Vinnie was a feisty bugger. And I was like, ‘John, let’s get out of here. Just leave. We’re on their field. Don’t.’ We ended up watching the rest of the game, which was a phenomenal game. John was still a little upset about it.”

Hardaker laughs. “Vinnie told them to fuck off.”

With Thelan at quarterback, Leeds won seven consecutive games to reach the play-offs in 1989. They triumphed away at Northampton Stormbringers in the first round of the play-offs — the competition’s first post-season fixture to go into overtime — only to narrowly lose at Birmingham Bulls in the semi-final. It was no coincidence that once Leeds had a team that could compete, they became derided as the ‘bad boys’ of the league.

“We got a sticker made that said, ‘Nobody likes us but we don’t care,’” says Hardaker. “That was in 1989, and it became the slogan for the 1990 season. We played incredibly physically. In fact, there was an idea that the very first play of the game, the three defensive linemen — we were all like wrecking balls, all about 5’10”, all about eighteen-stone — on the first sound, just smash the opposition centre. Invariably the penalty went against the offence because the referee wouldn’t think all three of us jumped offside at the same time, they’d think the offence must have moved the ball. So they’re starting off with the centre smashed and dazed, five to ten yards back from where they started.”

Thelan puts it more succinctly. “Leeds would punch you in the mouth.”

The Cougars relished their reputation, even if it often preceded them amid suspicions they were being unfairly singled out by officials. “The referees were always looking for us,” says Hardaker. “I remember one giving a penalty against me and saying, ‘I can’t see you holding, but I know you are.’ I said, ‘If you can’t see me, how can you throw the flag?’ We got a really, really rough time with the referee.

“The league was very political. There was more money in the south, but the real powerhouses were in the north. It needed organisation by a completely independent body. And it didn’t have that. It had people at the organisational level who were part of clubs. And that never works. I didn’t think we got a fair shake from the league, certainly. And maybe because when we went down, we were vocal, you know, with some of the southern teams. Colchester, who were nothing of a team, had all the power because their chairman was the chairman of the league. We didn’t like each other. I’ll leave it at that.”

If the 1989 season gave Leeds a foundation to build on, the following year proved the Cougars couldn’t escape the DNA of their city. “It just got to be really, really, really ugly,” says Thelan. Before the campaign began, Chuck Brogdon was told his services as head coach were no longer required. He was replaced by Dan Moore, an import who became player-coach, while Brogdon was promptly appointed by the same Birmingham Bulls team that had just beaten Leeds in the play-offs.

“Chuck got greedy and wanted all of the sponsorship money,” says Hardaker. “We said no and he went to Birmingham then. Chuck always said that I’d favoured Dan to come across as a head coach. The fact of the matter was, at the meeting, I’d argued that we needed to keep Chuck and that the owner, Peter Haddon, needed to work with him and work out what we could do. And that made Peter ask, ‘Is there an alternative plan if it all falls through?’ I said, ‘Well, yeah. Dan said if Chuck’s not here, he’ll come back and coach.’ Peter said leave it with me. Next thing I know, Peter’s been in touch with Dan, who’d been here for two years playing, and said, ‘Right, Dan’s coming over as a player-coach, and I’ve told Chuck we won’t be needing his services.’ Oh, okay. That isn’t really what we agreed at the meeting, but it’s your team and you’re the owner, I’m just the administrator.”

Brogdon wasn’t the only one to leave. The Manchester Spartans were trying to build a team of ‘Great Britain All-Stars’; amid allegations of poaching and illegal approaches, Tiggy Bell headlined a quartet of Cougars who defected across the Pennines. Bell had been Leeds’ star player of their first six seasons, but his exit opened the door for another import.

“Because Tiggy went, Dan came across and brought Chris Thomas with him that year, which made such a difference,” says Hardaker. “He would average 140 yards a game, every game, without fail. He was an absolute physical monster. CT was, for me, the best player that ever played in this country. He was head and shoulders above everybody else. He’d been at the Dallas Cowboys, and then on the last night of the training camp, they told him he had been cut because they’d managed to sign a big running back. So Chris got cut, came across here, and played for us for two years.”

There was at least one chance to relax during the off-season, as Hardaker led a trip to Cincinnati to meet the Cougars’ sister team, the Bengals. “Every team in the Budweiser League were allied to one of the NFL teams. And Dan was the assistant strength coach of the Bengals. So we had quite a strong connection with them. We went over for a fortnight, twelve of us from the team, and we met a lot of the Bengals, went to the practice sessions, went to lots of social things with them.

“Somehow, a local radio station heard that some guys from England were there, who were playing gridiron over here. They invited us in, so we had an hour on the local radio in Cincinnati. And then a guy, Ed Brady, who was special teams captain for the Bengals, sort of hooked up with us. We finished up at a party with him and all the first team players. I thought I was a big lad then, until I got there and saw some of them. They were absolutely ginormous, they were enormous men. They were great. They were really friendly and just really supportive. They were good times.”

On the Cougars website there’s a reference to the trip as ‘The Beer Monsters Tour’. “I couldn’t possibly comment,” says Hardaker. Really? I’d read that he was one of the chief Beer Monsters. “Noooo!” he laughs. “Definitely not!”

The instability of the off-season continued throughout the year. Injuries struck, and while Leeds qualified for the play-offs, their record of five victories and five defeats fell well short of Chuck Brogdon’s Birmingham Bulls and Tiggy Bell’s Manchester Spartans, who won nine games each. In the first round of the play-offs, the Cougars were drawn against the Spartans.

“We hated Manchester,” says Hardaker. “We played them at Bramley earlier that year. I remember them getting down to about our six-yard line. We ran a gap eight, which meant the eight biggest men on the team would go and fill a gap opposite an offensive spot. We ran a gap eight for ten plays, just to stop Tiggy scoring. It may have been the most charged set of downs I’ve ever played. There were four men at a time tackling him. It was insane. He wasn’t happy.” Hardaker smirks: “Of course, we didn’t say anything.”

Leeds’ preparations for their play-off against the Spartans were indicative of the power struggle in a league that changed its structure, format, and rules year to year. Having already secured first place, Manchester forfeited their final regular season fixture to avoid having to travel for an away game at Glasgow. As a result, the league ruled that Manchester had forfeited home advantage in the play-offs, leaving Leeds just three days to find a venue, with their usual Bramley home unavailable while the pitch was being re-seeded. The Cougars arranged for the game to be played at Herringthorpe Stadium in Rotherham. On Friday they were still marking out the pitch and notifying press, only for the Spartans to obtain a court injunction against the league that ensured the fixture would be played in Manchester.

“It was a nightmare,” says Hardaker. “Our prep was just all over the place. Really, the league should have been strong and said, ‘We’re sorry, but you forfeited that game. You can’t go in the play-offs. Because although you finished top, you weren’t bothered about finishing top.’ It just made a mockery of it. They didn’t tell Glasgow they forfeited the game until the Thursday.

“It was ridiculous. They should have said, ‘No, actually, Manchester, you’re not playing. Leeds, you’ve got a bye.’ We couldn’t organise a home fixture in three days. Our organisation was complex. We had everything going for us. We didn’t play at some tuppence ha’penny stadium like Manchester did.”

Trailing 31-12 in the fourth quarter, the Cougars mounted a comeback and reduced the score to 38-36, only for a late Spartans touchdown to condemn Leeds to another play-off defeat. “We should have won it that year,” says Hardaker. “We should have won it in ’89, but we definitely should have won it in ’90. Even though we’d lost some players, we recruited some great players. It really should have been that year. Now I think about it, I’ve never sort of made that connection, but it was a Leeds United season: loads of promise, and we should have done much better than we did. We became known as the best team never to win the championship.”

Hardaker stopped playing the following year. “Steve Fox took my number 17. After only three games, he said, ‘I’ve given your number up, because I’m sick of getting smashed by people that have got a vengeance against you. They think I’m you.” By 1992, the Cougars were still playing fixtures but had essentially folded as a semi-pro organisation. In an attempt to attract TV broadcasters, the league had continued increasing the number of imports each team were allowed. Not only was it to the detriment of developing domestic talent, but it crippled the finances of clubs that knew they had to fill their quota of imports if they wanted to compete. “It was sad. I remember I was in the States when the news broke that it’s all falling apart, clearly because people couldn’t afford it. My only regret is there was no legacy to leave.”

“A lot of my heart is still in Leeds,” says Thelan, from his home in Battle Ground, Washington State, just north of Portland. “That was a group of people, Mick being one of the big ones, that embraced some crazy Americans that wanted to pursue a dream to come over. And it was, it was an awesome opportunity.”

“I miss it enormously,” Hardaker says. “It was a massive part of my life. I think if you spoke to anybody that played for any serious amount of time, it was huge. Really, really huge. I still go on holiday with lads I played with. Apart from my kids and family, it’s probably the most significant thing in my life.

“The fans were special and they followed us everywhere. The play-off game at Northampton, we got lost on the team bus and couldn’t find it. We had no sat nav. You’re wholly reliant on maps. We couldn’t find it. We eventually got there and got into the changing rooms, and I said to the lads, ‘There’ll be nobody here from Leeds if even we couldn’t find it.’ We run out there, there’s thousands of them! My wife was there. She’d gone down in the car with a mate and was there cheering. I was like, ‘How the fucking hell have you found this place? I couldn’t have found this place!’

“So yeah, the fans, it was that thing: We Are Leeds. Manchester had a couple of teams, Glasgow had a couple of teams, London had a couple of teams, Birmingham had a couple of teams. Leeds had that one team. We had one team in this area. They were great times. I’ve had my knee replaced and my shoulder is still a bit clicky, but they were great times with good people.”⬢

(This article is free to read from TSB magazine 2023/24 issue 02. To buy paper copies or read more, click here)

© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us