When the rapper MF DOOM passed away towards the end of 2020, Ash Kollakowski of the Belgrave Music Hall approached Leeds art collective Two Times, asking if they wanted to paint a mural on the side of the venue in homage to one of hip-hop’s most influential and enigmatic artists. Kollakowski loves DOOM so much he took the name of his promotions company, Super Friendz, from one of his lyrics.

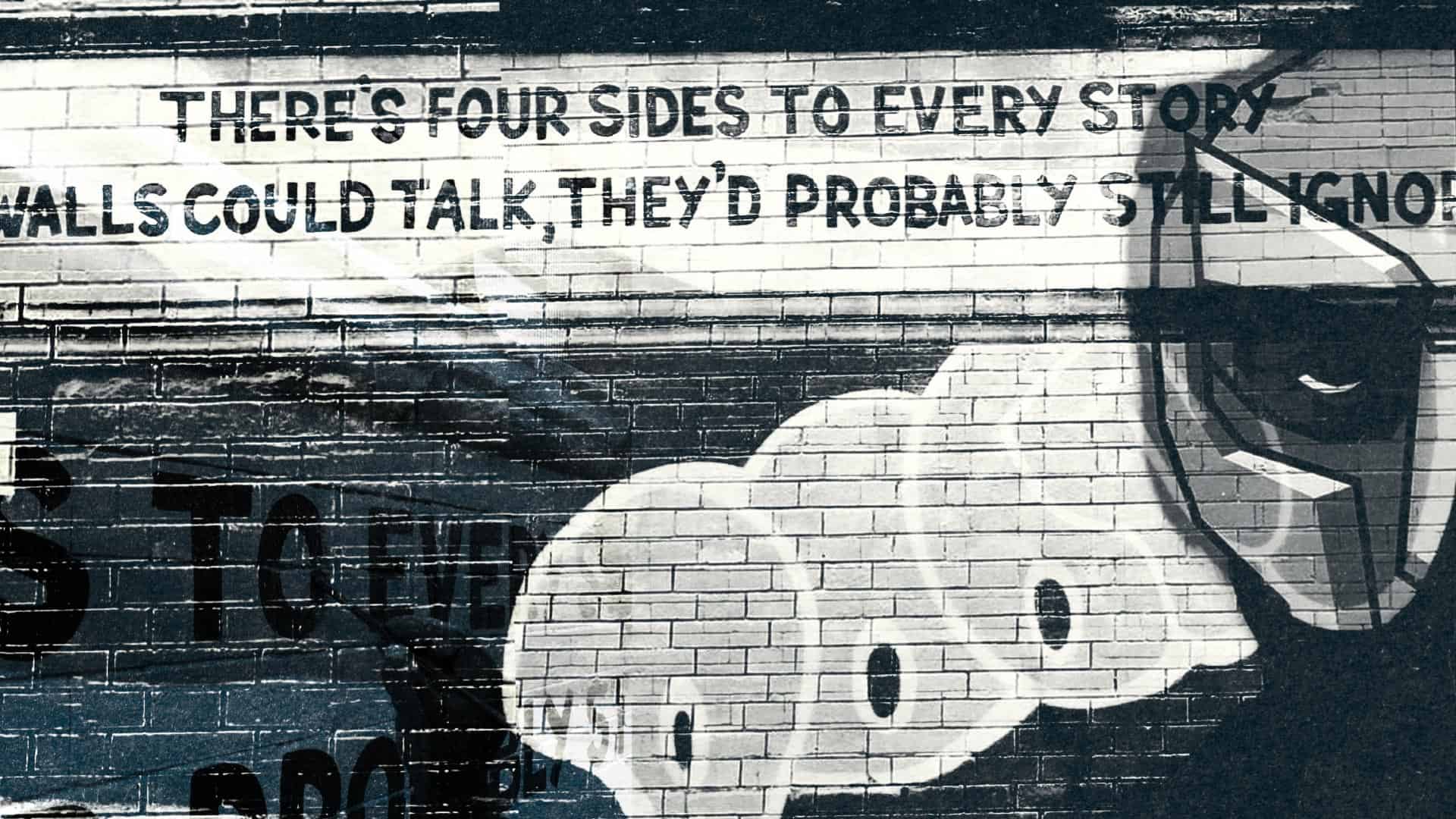

Two Times is a partnership between artists Benjamin Craven and Edan MF (the initials are a coincidence rather than a nod). They both share Kollakowski’s love of DOOM’s music, so after eighteen months of “sitting at home playing games” in lockdown, they ignored the “shit British weather” and got to work. If you walk down the side street next to the Belgrave, you’ll be greeted by the wall-high face of MF DOOM, who based his musical persona on the comic book character Dr Doom, hidden behind the trademark Gladiator mask he was never pictured without. Below is the lyric, ‘There are four sides to every story, if these four walls could talk they’d probably ignore me.’

“It’s weird the more I think about it,” Edan says. “When it’s just an idea and we’re coming up with the initial design, we don’t think much about it. I don’t want to use the word ‘organic’, but it is organic: it flows. When you’re painting something like DOOM, I don’t mean this in a spiritual way, but there was a gravity to it. It meant something.”

Two Times have painted murals in other parts of the city and at schools around Yorkshire, but the reaction to the DOOM mural was always going to be different.

“Seeing everyone posting it online, commenting, taking pictures in front of it, it’s quite overwhelming really,” Craven says. “And then we found out DOOM was supposedly living in Leeds for a bit. It means even more now. It’s mad thinking we could have been sat in the same bar as him having a pint. That’s what’s so fucking cool. It’s even more like a comic.”

Neither artist knew DOOM was rumoured to be living in Leeds when he passed away. When Craven first heard, he assumed his friend was talking “nonsense”. I had the same reaction when my friend Sam told me the same story shortly before Christmas. Sam talks a lot of bollocks, so I didn’t give it much thought until a couple of weeks later, when I remembered my housemate was a collector of DOOM’s records. He thought it was bollocks too. We both found it funny, ridiculous. A couple of days later we were having a pint in North Bar and he complimented one of the staff on a DOOM tattoo on their arm. “Did you know he was living in Leeds?” they replied. “It’s all over Twitter.”

All over Twitter was an exaggeration, but there were quite a few tweets relaying the same story, and the same disbelieving reactions. The details were sketchy: DOOM was supposedly living in Shadwell and apparently died in Leeds General Infirmary. The story came from a Facebook post by a Leeds DJ claiming he knew someone who had bought DOOM’s old house. And now I wondered. I started asking around, hoping to find out if it could possibly be true. Whenever I asked someone ‘in the know’, they started shifting uncomfortably, pausing before answering, as if trying to work out what they could say and what they definitely couldn’t.

DOOM died on October 31st, 2020, but the news wasn’t announced until New Year’s Eve, when his wife Jasmine posted a eulogy on his Instagram page, ending by writing he had ‘transitioned’ two months earlier. Geoff Barrow of the bands Portishead and BEAK> posted his own tribute, remembering how when he played with the latter at the Brudenell Social Club in Leeds, and was selling merch afterwards, someone asked him to sign a poster:

‘I asked if there was a name he wanted it to, he replied MF DOOM. I was like “What..who..why?” As I did I looked up and there was Doom stood there smiling. I’m like FUCK MATE LEEDS??? Whaaaaaa? What the fuck you doing here? We chatted and he was so lovely. I felt amazingly honoured that he had come to see us but still utterly confused that he was there? We chatted after we played and he seemed to dig it. As his music was a huge inspiration to me it was a night I’ll never forget and treasure. Someone extremely special has been taken away from us tonight.’

There was still no suggestion DOOM was doing more than visiting Leeds until the DJ’s Facebook post, a year later. One of the rumours I then heard was that DOOM was a regular at the Brudenell and could often be spotted standing at the back of gigs drinking a pint of Guinness. There’s a track on the DOOM album Mm..Food called Guinnesses, featuring the lyric, ‘I shoulda deaded it from genesis instead of hittin’ the Guinnesses.’ If DOOM was a regular at the Brude, Nathan Clark, who runs the place, says he didn’t know anything about it. He definitely saw him at the BEAK> gig — “I accidentally stood on his hand,” while DOOM was sitting on the floor, he says — but that’s the only time he remembers seeing him.

This is the problem trying to verify whether DOOM was or was not living in Leeds. I kept being told interesting details, then hearing a contradictory story. He was either at gigs in the Brudenell all the time or was only there once. Someone told me he was living in Shadwell with his wife, someone else said he was living with two guys who worked either as his managers or promoters.

It’s typical of the universe DOOM created. Fact and fiction are rarely distinguishable. The lines between his personas are blurred; he released music under at least ten different aliases. What we do know about his life is that he was born and named Daniel Dumile in London, and moved to New York with his family before he was old enough to make any memories in England. He started making music as part of the rap collective KMD, adopting his first persona, the unmasked Zev Luv X. Dumile’s younger brother, Dingilizwe, was also a member of KMD, going by the name SubRoc. In 1993 SubRoc was hit by a car and died in hospital, aged 19. The elder Dumile was spending the night in a cell after being arrested for a minor offence on an old warrant — “having an open can of beer or something,” his former manager Pete Nice told New York magazine. Upon his release, he was told over the phone by his mother that his brother had been killed. Disagreements with their record label meant KMD’s second album was never released. Dumile played it in full from a boombox next to the casket at his brother’s wake. When its release was shelved, he disappeared from the music scene. He reemerged towards the end of the decade as MF DOOM. For part of that period in between, he was essentially homeless. “When I write from a broke-ass point of view I’ve actually been there,” he told journalist David Ma. “When I spoke as MF DOOM, I spoke from those dark points of view in some ways I guess.”

MF DOOM quickly gained recognition beyond what Dumile had been exposed to with KMD. His debut album Operation: Doomsday is considered a cult classic. His 2004 release alongside the producer MadLib, titled Madvillainy, became his iconic record. Despite the success, he maintained his mystique. There are stories of musicians working alongside him for days in studios and never seeing him without his mask on. It wasn’t unknown for him to send different people wearing the mask to perform in his place at DOOM shows, a trick he seemed to enjoy more than the paying audience. MF DOOM once spent an entire day in a hotel room conducting different interviews and photoshoots, only for the creative director for one magazine to zoom in on the cover photo and realise the eyes of a different person were behind the mask. DOOM later admitted he had sent his hype man/bodyguard Big Benn Klingon instead.

It’s a trick DOOM may have been repeating in Leeds. He was known to be a collector of remote control cars, once reviewing different models for an issue of a dedicated magazine, giving each one a rating from one to five DOOM masks. I visited a shop in Leeds selling RCs priced up to almost £4,000, where I’d heard DOOM might have shopped. A member of staff told me it was true, but asked neither he nor the shop were named. He told me DOOM sometimes sent one of two friends he was living with on his behalf. They all wore DOOM rings, he said, but only Dumile’s was gold. Apparently there was once a problem with one of his orders, so DOOM left a one-star review on TrustPilot.

DOOM rarely toured abroad. Despite living in America for 35 years, he never gained permanent citizenship. The website Pitchfork unearthed documents that show the federal government created a record of Dumile as a ‘deportable alien’ when he was just three years old. After a run of shows in Europe in 2010, he was refused entry back into the US and was separated from his wife and three children. He moved to London, where he kept in touch with his family via Skype calls and their occasional visits. “This is a new place for me,” he told The Guardian in 2012. “I have no friends here apart from the dudes at my record label, and I didn’t go to school with no one. Nobody knows me — I’m incognito.” Five years later, his son, Malachi Ezekiel Dumile, passed away aged fourteen. ‘Safe journey and may all our ancestors greet you with open arms,’ DOOM wrote on Instagram. ‘One of our greatest inspirations. Thank you for allowing us to be your parents.’

The musician Questlove once suggested Dumile adopted the MF DOOM persona in the 1990s as a way of coping with the tragedy of his brother’s passing. The creator of Marvel’s Dr Doom, Jack Kirby, said he modelled the character’s appearance on death, with the “inhuman-like steel” of his armour replacing the warmth of a human touch. DOOM himself said he used the mask because he was growing tired of the trend of rappers being more focused on what they looked like rather than what they sounded like. He never knew what his favourite emcees looked like when he was growing up listening to their music, and it never mattered. Hiding his face behind a mask meant audiences had to listen to what he was saying if they wanted a glimpse of who he was. If Daniel Dumile could remain anonymous behind the mask, it allowed him to write from the perspective of different characters without it feeling jarring to his audience, because they never knew who he was in the first place. “It’s important to remember that I’m not DOOM,” he told David Ma. “I just write as this evil supervillain rapper named DOOM.”

These divergent personalities make it even more difficult to work out if DOOM really did move to Leeds. Amid all these different characters, it’s not clear exactly who people think was living here.

The cause of his death has never been made public, but it was suggested to me that Dumile left London for Leeds because he knew he was ill and wanted to live somewhere quieter. Whether or not that’s true, Leeds is the ideal place for someone wanting to live and be left alone. The Leeds musician Katie Harkin perfectly described the city’s nonchalance towards its local talent on the podcast Turned Out a Punk. “There’s a thing about Leeds, and Yorkshire in general, where there’s [an attitude of], ‘What do you want, a medal?’ This feeling of anti-pride, not wanting to be too much of a show off.”

It’s one reason Marcelo Bielsa has been able to make Leeds his home for longer than anyone expected. Everyone knows where Bielsa lives, shops, and eats, but he generally gets left in peace because the artistry of his football speaks for itself. During lockdown, Bielsa has said, a woman called Bella regularly left homemade soup on his doorstep, but did she knock for a selfie, advertise the gesture on social media? It wasn’t about who he was. It was about a neighbour knowing he was far from his home and family in a pandemic.

Two Times’ Edan MF says he has heard stories of Dumile happily sitting in bars, minding his own business, occasionally chatting to people who had no idea who they were talking to. “In a place like Leeds, he’s just another bloke,” he says. Like Black Flag’s Henry Rollins living in the Harolds in Hyde Park or Liv Tyler drinking in the New Headingley Club, DOOM living in Shadwell has been added to Leeds folklore, and it no longer really matters whether it’s true or not. The effect is the same.

If quiet anonymity was the attraction for Dumile, Leeds was also a fitting home for the character on which he based his alter-ego. Dr Doom is Marvel’s equivalent to the great anti-heroes of Leeds writers David Storey and Keith Waterhouse. In Storey’s novel This Sporting Life, Arthur Machin is the self-sabotaging tyrant of Primstone’s rugby league team, yearning for power, status, and recognition. Put Machin through a Marvel filter, you get Dr Doom, feared ruler of the planet Latveria and arch-nemesis of the Fantastic Four, whose conscience always prevents him from completing their destruction the closer he gets to doing so. Creator Jack Kirby once drew Dr Doom without his mask, revealing just a single small scar on his face. Dr Doom’s main flaw is being a perfectionist, according to Kirby, which is why the small blemish is enough for him to hide his face, more from himself than others. When MF DOOM completed the album Madvillainy with MadLib and was preparing for its release, he decided to halt the process so he could redo the lyrics to the entire album, convinced they could be improved. I can’t help thinking DOOM and Marcelo Bielsa might have enjoyed each other’s company.

Whether DOOM lived in Leeds or not, he has a tangible influence on the city. As well as Two Times’ mural at the Belgrave, DOOM graffiti appeared on bus stops and walls following his death. Tribute gigs were held by artists from the local jazz scene inspired by his music. Leeds Conservatoire lecturer Rob Mitchell is partly responsible. Mitchell is the leader of Abstract Orchestra, a group of musicians blending jazz instrumentation with hip hop beats. They have released two albums covering DOOM’s Madvillainy record with Madlib. Mitchell started using some of his Madvillainy arrangements in his teaching, and DOOM’s influence crept into the work of his students, who have played live with Abstract Orchestra or performed their own shows in homage to DOOM.

“I got obsessed with his flow,” Mitchell says. “He’s got such a unique flow and rhythm. The way he structures his lines really stuck with me, because it feels really jazz. The way he flows is just like a saxophone improvising. It feels really free and really loose, and there’s little moments of juxtaposition or a little junction where he visits something then comes back to the main theme. That really intrigued me as to how he was doing it. Not that I figured it out.”

Mitchell once worked indirectly with DOOM, communicating via two different sets of management, when remixing DOOM’s vocal from a track called Air over one of his own compositions. It was a back and forth process requiring numerous tweaks until DOOM was happy.

“He’d listened to it and apparently he liked it,” Mitchell says. “I had to do quite a lot of manipulating of that original a cappella track because of the feel of the track that I’d done. It was quite different from the original. There were requests for moving things around rhythmically, so his flow actually adapted to what I’d written. It was quite an unusual process and like nothing I’d ever experienced before in terms of the requests. I had to send multiple versions of what I’d done with chopping up his vocal for it to eventually get the green light.”

Mitchell was waiting to receive clearance right up to his record label’s deadline. “I was literally sweating buckets, thinking, ‘Oh man, I can’t miss this opportunity. I’ve come so far down this pathway, I just can’t miss out on it. I’d be absolutely gutted.’ People say ‘at the eleventh hour’ — it was literally 11pm on the Sunday night, when it was going to press on Monday morning, I got the email from management saying, ‘Yeah, DOOM says go’. So it managed to make the cut, which I was just so happy about.”

Given the convoluted process of communicating through so many different people, Mitchell is reluctant to claim his remix of Air as a direct collaboration with DOOM, a dream that so nearly became a reality.

“I still have an album that I’ve been working on for a while. It’s sort of shelved at the moment, but there’s a track on there that I wrote for DOOM. I said to my label, ‘I want DOOM on it. We’ve got to do this.’ They were like, ‘It’s going to be expensive, but we’ll find out how much it will cost.’ I’m not going to say how much, but it was a lot of money.”

While Mitchell was trying to persuade his record label to cough up, DOOM agreed via his management to appear on the track if the label paid the fee. “By the time my label would come around to it, unfortunately he’d passed. I was like, ‘Right, we’ve got the green light. We’re all go.’ Then there was no communication from October 31st.”

The impact on Mitchell of DOOM’s death went far beyond the frustration of an unfulfilled collaboration. “I was devastated, absolutely devastated,” he says. “He is one of my heroes. He’s an icon in a number of ways, and him and his music mean a lot to me. It felt like a personal loss, even though I didn’t know him personally. I didn’t even have direct contact with the man. Like a lot of people I knew very little about his personal life, but by what bits you see and read he seemed like the loveliest guy. He had so much to offer and was just such an interesting person that, yeah, I felt devastated, and still feel impacted by the big gap that he leaves behind.”

When Mitchell was in touch with DOOM’s management, he had no idea he might have been emailing people living in the same city as him, completely unaware of the rumours until seeing the infamous Facebook post by the DJ from Leeds.

“I think people find it so hard to comprehend that he could have potentially lived here, because he could have potentially lived anywhere,” he says. “I think that’s why it seems so difficult to to get to grips with, because not only do we hold him in such high regard, but he has this mythical approach to his persona. Of course there’s wearing the mask, but more than that, the persona of the supervillain, all these different personalities he had, the comic iconography of it, the fact he is etched as a cartoon character, as this thing that isn’t tangible. When you think, ‘Oh, he was living in Leeds around the corner,’ you think, ‘But that doesn’t make any sense.’ It’s so obscure, isn’t it? It’s just such an unusual thing to try and comprehend. I think that adds to the myth.”

The most exciting thing I was told about DOOM in Leeds was that he continued making music here. Mitchell’s story suggests he was still actively recording, but DOOM could still have been living anywhere while recording a vocal for Mitchell’s album. Part of me is desperate to know what DOOM’s music would have sounded like if he had been writing and recording in Leeds. Colloquialisms and British cultural references were seeping into his music when he was living in London. His album Keys to the Kuffs features tracks called Guv’nor and Rhymin’ Slang. My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding gets a mention on the song Banished. The UK has even infiltrated the world of Dr Doom, with more recent issues of the comic referring to Brexit and a foe called Union Jack.

If DOOM was recording in Leeds, I like to imagine he was writing about drinking Guinness in the Brudenell, racing remote control cars in Shadwell, and murderball. But the more I think about it, the happier I am that I’ll never know. Daniel Dumile lived his life playing with the most tantalising aspects of myth and mystery. Nobody will know for sure if they ever casually chatted to a supervillain in the Belgrave on a Saturday night, but now we all hope we might. Whether it’s true that he lived here or not, the myth is stronger. It gives Leeds a unique place in the universe he created, and left behind for everyone else to explore. ⬢

(This article is free to read from The Square Ball magazine 2021/22 issue 6. Click here to find out how to support us with TSB+)© 2009-2023 The Square Ball Media Limited | All Rights Reserved | Contact us